Cheap booze prices to rise as MSPs raise minimum cost

MSPs are expected to vote later to increase the minimum price at which alcohol can be sold by 30%.

Scotland was the first country in the world to set a minimum price for alcohol - a move that came into force in May 2018.

For the past six years, the price per unit of alcohol has been 50p but MSPs will vote on putting it up to 65p from the end of September – a move designed to reflect rises in inflation.

The change will see the minimum price for a bottle of vodka rise from £13.13 to £17.06 and a standard can of lager will go up from at least £1 to £1.30.

Doctors and alcohol recovery groups supported the price increase but told BBC Scotland News there was a “grave concern” that prevention services for those at the most risk were insufficient.

Each week about 700 people in Scotland are hospitalised and 24 die as a result of alcohol, official statistics show.

The Scottish Deep End Project – a group of GPs working in the highest areas of deprivation – said alcohol-related harms were at a “crisis” level in Scotland and better investment in services was “urgently” needed.

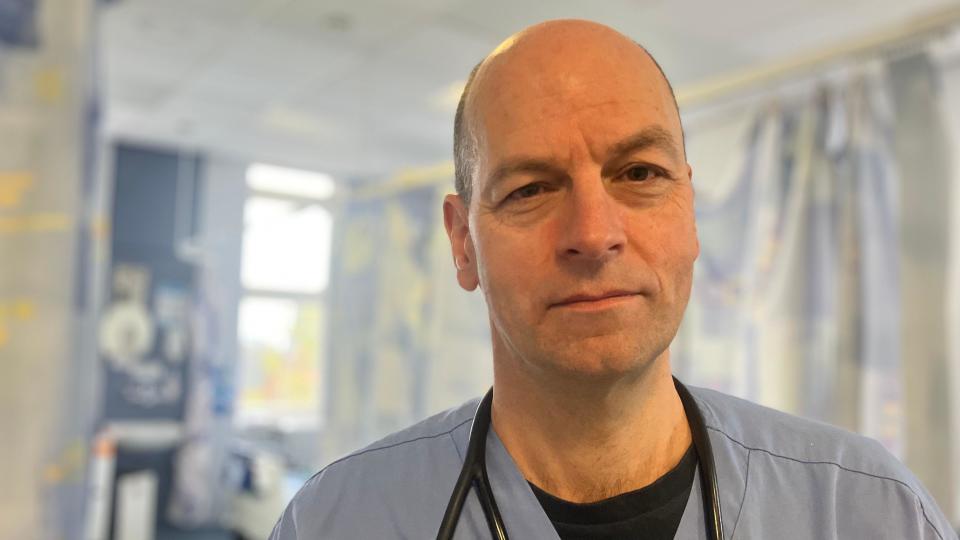

Dr Ewan Forrest, a consultant liver specialist at Glasgow Royal Infirmary, said: “There’s no doubt about the benefit of minimum unit pricing, but in isolation it’s not enough."

What is the evidence for MUP?

Academics have been evaluating the impact of minimum unit pricing (MUP) for some time, and last year Public Health Scotland (PHS) collated 40 studies to examine the policy’s effect on health, business and public attitudes.

Best estimates suggest that MUP has saved an average of just over 150 lives a year since its introduction and avoided more than 400 hospital admissions per year.

In 2022, the last year for which figures are available, there were 1,276 alcohol-related deaths in Scotland, the highest level since 2008.

However, PHS said the picture would have been even worse without MUP.

But the report also acknowledged there was “limited evidence to suggest that MUP was effective in reducing consumption for those people with alcohol dependence”.

What is the opposition to the move?

The Scottish Conservatives have previously cast doubt on the conclusiveness of the data on MUP’s effectiveness and argue increasing it to 65p "disproportionately penalises responsible drinkers during a cost of living crisis”.

“It is clear, contrary to SNP government claims, that MUP is not the silver bullet for problem drinking,” said their health spokesman Dr Sandesh Gulhane.

“It has failed to curb alcohol-related deaths in Scotland, which have soared to their highest levels since 2008.”

Dr Gulhane added that there is evidence to suggest that some problem drinkers are skipping meals in order to buy alcohol.

Meanwhile, although retailers have broadly supported the 50p rate, they have warned the increase could harm struggling local businesses.

The Scottish Grocers Federation (SGF) argued the analysis carried out on MUP, coupled with changes to drinking habits in recent years as a result of Covid, has “not been sufficient” to justify the increase.

The SGF said: “Restrictions and higher prices inevitably come at a greater cost to doing business, putting more pressure on budgets and struggling household incomes.”

What do doctors think?

Doctors support the increase, arguing that the effects of the 50p rate have been eroded by the rise in prices over the past six years.

Dr Alastair MacGilchrist, a consultant liver specialist and chair of the Scottish Health Action on Alcohol Problems (SHAAP), said the uprating to 65p would save more lives and avert “hundreds” of hospitalisations each year.

Dr Forrest, from Glasgow Royal Infirmary, said the number of people being admitted to his ward with alcohol-related liver disease decreased during the first years of the policy and there was “no doubt” about the benefits of MUP.

What do those in recovery say?

Joshua, who is 28, has just 10% of his liver left after years of abusing alcohol.

From his hospital bed in Glasgow, he told BBC Scotland he thinks the minimum price of alcohol should increase further still.

But he also believes there should be a clamp down on how alcohol companies are allowed to advertise.

“How can you put on a packet of cigarettes all these warnings, but on a bottle of alcohol all you get is a circle saying ‘drink responsibly’?" he said

“I think they should be putting stuff like 'liver disease is a fatal condition'.

“They make an enormous amount of money through us buying booze and it’s everywhere, it’s marketed everywhere, it’s the adverts. Take those down.”

Joshua used to be teetotal, but says after watching his uncle die from alcohol addiction and experiencing years of homophobic bullying he began drinking.

“I would just sit at home and drink litres of vodka, I was too afraid to leave my front door,” he said.

He’s determined to stay sober, and hopes that young people learn from his mistakes.

“I try to not worry but deep down it petrifies me what could happen," he said.

Rod Anderson has been in recovery for 10 years and think there are “arguments either way” about the effectiveness of MUP.

“Would it have made any difference to me? No it wouldn’t have, I was going to drink no matter what the price was,” he said.

“But we do know the consumption of alcohol is price sensitive, so putting it up is a good idea.”

Mr Anderson is now director of Recovery Coaching Scotland and helps people across the country struggling with substance abuse.

“In the third sector in Scotland, around drug and alcohol treatment, we’re a sector that constantly struggles for funding and the landscape for that is getting worse,” he said.

He argues an opportunity is being missed to use the funds raised by MUP to fund these organisations.

MUP does not generate any money for the government and therefore can’t be used to fund tackling the health and societal issues caused by excessive drinking.

Campaigners and Scottish Labour have argued for some time that there should be a public health levy on alcohol sales to ensure income generated by MUP can fund such services rather than go to retailers.