Jesus on a fighter jet: South Beach art show explores how religion justifies war

Al Farrow gets his bones and guns second hand.

The San Francisco-based artist puts his engineering background to good use as he squashes bullets into roof shingles and pistols into church door frames. The majestic flying buttresses of his Gothic-style mausoleum are guns, too. A Catholic-style reliquary is bedazzled with blue-green bullets, a fitting final resting place for the skull of a fictitious Patron Saint of War. And a sculpture of Christ is crucified on a fighter jet.

As war and conflict rage around the world, the artworks at “Loaded,” Farrow’s solo exhibition at VISU Contemporary Gallery on South Beach, are as relevant as ever. But his artistic inspiration is a tale as old as time.

“All the religions are equally guilty in the hypocrisy of using religion to incite people to fight, and that goes all through history and prehistory. It’s that particular hypocrisy that really affects me,” Farrow said. “You look at the 10 Commandments and it says, ‘Thou shalt not kill.’ Well, all the religions send their chaplains into the army, bless the soldiers and tell them God’s on their side. God’s on everybody’s side.”

Farrow discussed his work with guests at the exhibition’s opening night earlier this month. The exhibition, which is available to view by appointment, is open until May 25.

As the Israel-Hamas war continues following the Oct. 7 attack — which has lead to an estimated 34,000 Palestinian deaths, according to the Gaza Health Ministry, a looming famine in Gaza and rising tensions and protests across the United States — the gallery was a bit concerned that an exhibition that explicitly discusses religion and violence would offend some people, said VISU co-owner Bruce Halpryn. But that hasn’t been the case.

Instead, Farrow’s artwork does what good art should do, Halpryn said. His art is “a tool to initiate social discourse.”

“I don’t think the role of art is to be a pretty piece over the living room couch,” said Halpryn, who has been collecting Farrow’s work for 15 years. “The type of work that I’m interested in is the type that makes you reflect on what’s going on in the world around you. And every time you look at it, you see something different.”

Above all, Halpyrn stressed, Farrow gets his point across as respectfully as possible. Farrow does not disparage any religion, the artist said, and he certainly doesn’t want to disrespect anyone’s beliefs. Rather, the subject of his critiques are the institutions that use religion to justify violence and war.

Practically every organized religion is guilty of this sin, Farrow said. That’s why he references several religions in his work, particularly the Abrahamic religions of Christianity, Islam and Judaism, by sculpting reliquaries, churches, mosques and synagogues.

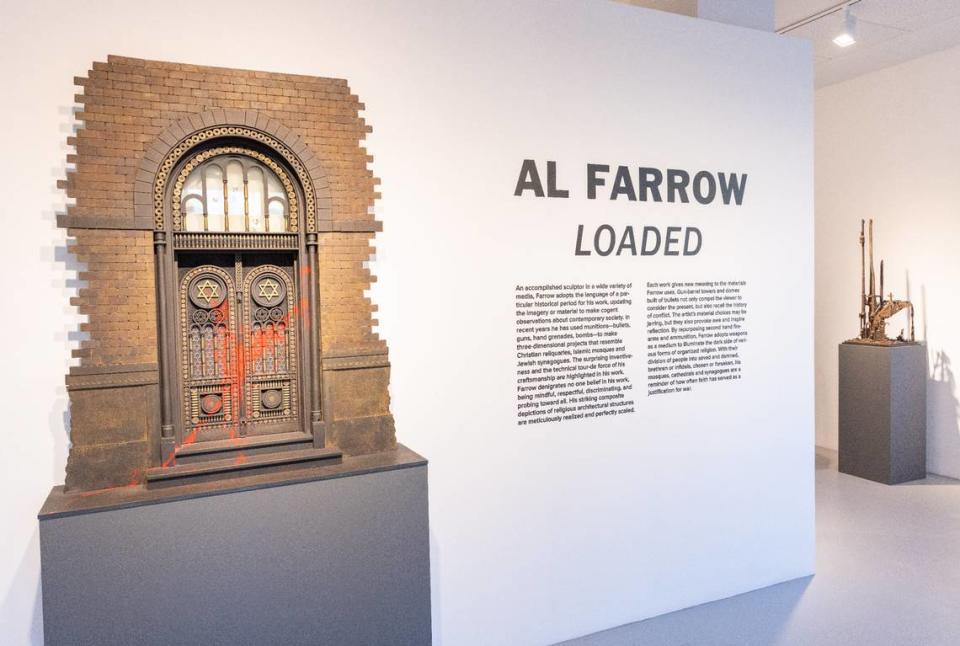

The exhibition also examines when violence is inflicted upon religious groups. The first sculpture in the exhibition that greets visitors is a jarring example of that.

A gash of red paint is splattered across the door of an otherwise beautiful synagogue. The decorative glass arch above it is pocked by gunshots. Based on the Nazi rampage of Kristallnacht, Halpyrn said, the grand synagogue door made of steel, gun barrels, cartridge shells and bullets is from Farrow’s series of vandalized houses of worship.

Also on display is a menorah of shell casings and barbed wire, reminiscent of concentration camp fences, Halpyrn said. On the floor, directly underneath the menorah, is an ammunition box filled with white candles. On the wall across from it, empty shell casings are retrofitted into Jewish mezuzah doorposts, which hold a piece of parchment inscribed with Hebrew verses from the Torah.

Though there are several artworks in the exhibition that reference Christianity and Judaism, the gallery wasn’t able to include any of Farrow’s Islamic sculptures. As Halpyrn put it, Farrow’s recreations of mosques are so beautiful, they’ve all been sold already.

Like many in his generation, war was omnipresent in Farrow’s life. He was born in 1943 in Brooklyn, New York, during World War 2. In his early 20s, he protested the Vietnam War and avoided conscription. Today, now 80, his art reflects his longheld anti-war stance. “I didn’t want to fight in anybody’s war because I didn’t see it as moral,” he said.

Farrow was not raised in a religious household, he said. In fact, his parents didn’t force any particular belief system on him. As an adult, Farrow identifies as spiritual, though he does not belong to any organized religion.

“I’m a free thinker,” he said. “And I thank my parents for allowing that because I did grow up to be very critical of society.”

Farrow’s works on religion and violence were inspired by a 1995 trip he took to Italy, where he saw a Catholic reliquary containing the withered finger of a dead saint. (In Catholicism, there is a practice of keeping relics that have belonged to saints — like their bones — in ornate vessels.)

Several works on display reference this practice. Halpyrn invited guests to shine their phone flashlights through the mausoleum glass. A real human skull sits inside. Another ornate reliquary in the show displays a finger bone it calls “The Middle Finger of Santo Guerro.”

Farrow has sourced the bones, ammunition and guns from specialty stores and odd, old collections. Years ago, he would get bones from a place in Berkeley, California, called The Bone Room, which used to sell all types of bones and artifacts for scientific purposes and film sets. One time, a woman called him asking if she could give him her deceased husband’s guns. Another time, a man gave him an entire articulated human skeleton. He carried the skeleton into his car, sat it in the passenger seat and clicked the seat belt. Safety first.

Some of Farrow’s art supplies have seen the horrors of war. A rusted helmet with gaping holes is perched on top of one artwork — a grim reminder of the fate of the soldier who wore it into battle. Farrow pointed at a sculpture meant to resemble a burnt church. It was made with three real rifles from the Battle of Verdun, the longest battle in World War I.

Farrow noted that organized religious institutions are often motivated, not by faith, but by more earthly matters: “It’s about power, control and money.” Though religion certainly plays a role in many conflicts, especially in the Middle East, issues of land and politics are the real driving factors.

“They’re using religion to get everyone upset, upset enough that they’ll actually kill somebody,” Farrow said. “That’s power. That’s the power of organized religion.”

Despite the difficult subject matter, Farrow said he’s received very little objection to his work over the years. The only controversy that came to mind was concerns that some of the bones in his work may have belonged to Native Americans, he said. What surprised him once was a time when a religious woman told him that she had never noticed the connection between religion and war before she saw his artwork.

Ultimately, the goal of his work is to just get people thinking, he said.

“I don’t really care what exactly they go away thinking, what I care about is that I made them think,” Farrow said. “Because if they’re thinking, they might come to the right conclusion. They might not, but they might.”

‘Al Farrow: LOADED’

Where: VISU Contemporary, 2160 Park Ave., Miami Beach

When: On view until May 25

Info: Free entry. Available to view by appointment Wednesday to Sunday. Email info@visugallery.com or call 305-496-5180 to make an appointment.

This story was produced with financial support from individuals and Berkowitz Contemporary Arts in partnership with Journalism Funding Partners, as part of an independent journalism fellowship program. The Miami Herald maintains full editorial control of this work.