More Democrats here, more Republicans there: How Miami’s voting districts are changing

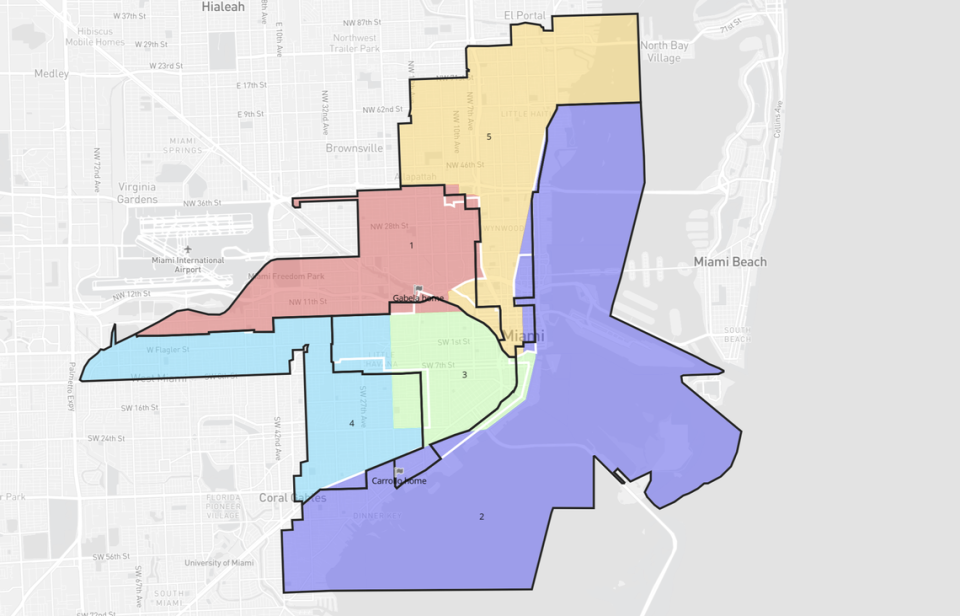

A proposed new voting map that will go before the Miami City Commission on Thursday as part of a settlement in a racial gerrymandering case makes minor changes to demographics and political affiliations in districts for the city’s five nonpartisan seats, drawing one commissioner out of his district and affirming the residency of another commissioner whose home was cut out during the last election cycle, sparking litigation and accusations of political antics.

The new map was agreed upon as part of a proposed settlement in a federal lawsuit against the city filed by voting rights activists represented by the American Civil Liberties Union. The settlement would mark the end of a contentious legal battle, while costing the city over $1.5 million in attorneys’ fees racked up by the plaintiffs. It also closely coincides with last month’s ouster of City Attorney Victoria Méndez, who had defended the previous map. With the exception of Carollo, commissioners indicated to the Miami Herald that they plan to vote to approve the settlement and the new map.

Last month, U.S. District Judge K. Michael Moore ruled that Miami’s voting map was racially gerrymandered and ordered the city to toss it out. Before the ruling, commissioners had openly stated that the voting map was drawn to ensure the five-member commission comprised three Hispanic, one white and one Black commissioner to guarantee racial diversity of the board’s membership — a policy that Moore said violated the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

At first blush, the new map appears to closely resemble the previous version. But Nicholas Warren, an attorney for the ACLU, said the new district lines “follow major roads and easily recognizable boundaries, rather than dividing communities and forming irregular appendages.”

For example, U.S. 1 now separates District 2 from Districts 3 and 4 completely, whereas previous versions had portions of the boundary dipping into Coconut Grove, dividing East and West Grove into separate districts. The new map also uses the Miami River as a boundary between Districts 1, 3 and 5, unifying the Overtown neighborhood.

Commission Chairwoman Christine King celebrated the unification of Overtown, saying residents “will not be negatively impacted by the redistricting.”

“The Overtown community has suffered enough,” King said in an email. “Hopefully, the proposed settlement will resolve the dispute, once and for all. We must move on from this litigation and continue our focus on serving constituents, as this has always been my top priority.”

But not all neighborhoods are in the same district under the proposed new map. By using 22nd Avenue from Northwest Seventh Street to Coral Way as a boundary, the settlement map pushes more of the Little Havana neighborhood into District 4.

Residents in the Shenandoah area were disappointed to learn their neighborhood — which had been split between Districts 3 and 4 — will remain divided, this time with a larger portion in District 3.

“We were really hoping for unification of our neighborhood under one district,” said Lindsay Corrales of the Shenandoah Homeowners Association.

District 2 Commissioner Damian Pardo called the voting map settlement “the light at the end of the tunnel.”

“I’m just super excited we’re turning that page,” Pardo said. “It’s so important to move beyond this impasse.”

Demographic changes

Under the proposed settlement, the incumbent commissioners would continue to serve their current terms despite the map changes. While some of the officials celebrated the new map, others expressed skepticism.

District 4 Commissioner Manolo Reyes said the previous map ensured diversity on the City Commission and that his primary concern “is that we have proper representation of every ethnic group.” He said a map that doesn’t guarantee such representation could lead to an all-Hispanic commission in the next one to two election cycles. However, Reyes added that he will likely vote for the new map, given the circumstances. “What alternative do I have if we are ordered by a judge to reach an agreement?”

The proposed new map makes only minor changes to the demographics of voting-age citizens in each district, a Herald data analysis shows.

Any changes to the racial makeup of a district are inadvertent, according to Warren of the ACLU. “No district was drawn to achieve a specific racial composition,” he said.

A Hispanic supermajority would remain in Districts 1, 3 and 4. District 5 would remain majority Black, with the percentage of Black voting-age citizens decreasing slightly, from 57.4% to 56.5%, according to 2020 Census data.

District 1 could change party lines, going from 49.4% to 50.5% Republican, according to data showing the 2020 presidential election results within the new boundaries. The population of voting-age citizens would be 86.6% Hispanic, a marginal increase from before.

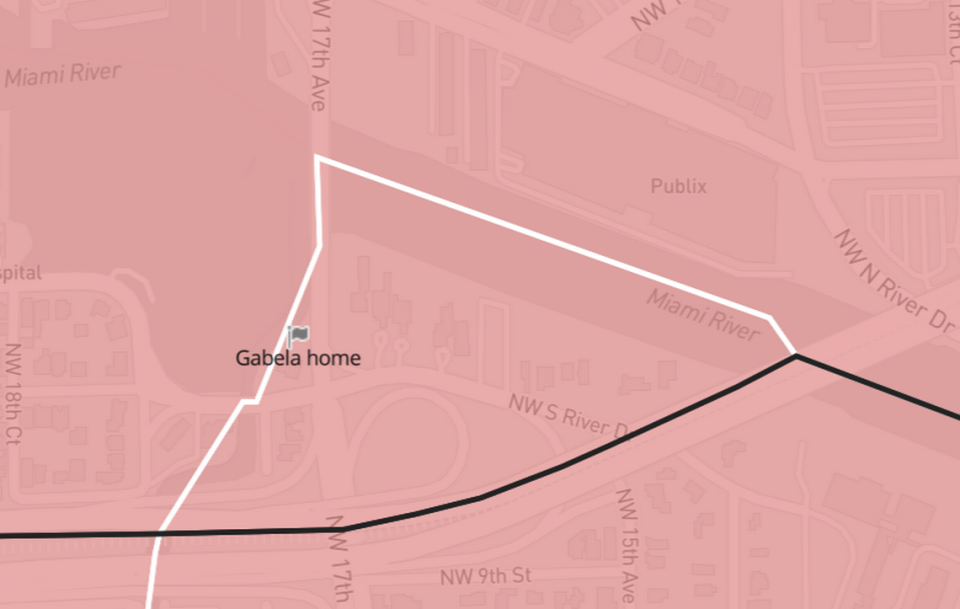

The redrawn map also affirms the residency of District 1 Commissioner Miguel Angel Gabela, who unseated Alex Díaz de la Portilla in November. Last summer, months after Gabela had begun campaigning for the District 1 seat and a federal judge ordered a temporary map be drawn, commissioners approved a map that drew his home out of District 1. That sparked multiple lawsuits over the validity of Gabela’s commission bid. By the time votes were cast in a runoff between Gabela and Díaz de la Portilla in late November, the courts had confirmed that Gabela could run for the seat.

Gabela said the controversy surrounding his residency was a “political trap.”

“I just hope for the future, going forward, this doesn’t happen again to anybody,” he said.

District 3, represented by Commissioner Joe Carollo, would lose around 1,500 Hispanic voting-age citizens and about 300 Black voting-age citizens, gaining approximately 1,250 white voting-age citizens. Still, the district would remain 79.8% Hispanic, a slight decrease from 82.7% under the 2023 map.

“They decided that District 3 was their turkey — the one that they could slice up,” Carollo said.

District 3 would also become slightly bluer, going from 52.8% to 54.4% Democrat, according to 2020 presidential election results.

Carollo, a Republican on the nonpartisan City Commission, told the Herald that he believes the plaintiffs set out to make “ideologically gerrymandered districts” and redrew his district lines intentionally “so that liberal Hispanics will have an opportunity to win” District 3 and ultimately create a majority-Democrat commission.

In response to those claims, the ACLU said its clients have “fought for district lines that were fair to the communities that make-up our multi-racial, multi-ethnic and multi-cultural City. We have fought to improve the democratic process at the local level by requiring the use of maps that are fair and not racially discriminatory.”

The new map would put Carollo’s Coconut Grove home out of District 3 and into District 2 — a change that won’t affect the commissioner since he is term-limited once he finishes his current term, which ends in 2025.

That doesn’t prevent Carollo from running for mayor, however. Asked if he intends to do so, he told the Herald that he doesn’t “want” to run for mayor but wouldn’t go as far to say that he wouldn’t run.

Carollo kept his cards close to his vest when asked how he plans to vote on the settlement Thursday.

“You gotta leave some suspense,” he said. “If we tell them before how every vote’s gonna be, then nobody’s gonna watch.”

Miami Herald Associate Editor Joey Flechas contributed to this report.