How Miami-Dade students are feeding astronauts. Inside NASA-funded program at Fairchild

Not everyone can say they have had a direct impact on the International Space Station (ISS), a research facility that orbits the Earth.

But some students across the country do, thanks to a NASA-funded program called Growing Beyond Earth (GBE) that lets kids be scientists, experimenting with what astronauts can eat in space.

The research center at Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden in Coral Gables launched the program in 2015. And on Saturday, about 200 of the middle and high school students participating this year will meet in virtually — and in person for the first time since before the coronavirus pandemic — at Fairchild’s Arts Center to discuss their latest findings.

“I feel fortunate,” said Isabella Gonzalez, a senior at Hialeah’s iMater Charter High School, who has participated in Growing Beyond Earth since she was a sophomore. “If you would’ve told me in middle school that I would be doing research for NASA, I would’ve never believed you.”

Gioia Massa, a space crop production scientist at NASA’s John F. Kennedy Space Center on Merritt Island, said the program started when a Fairchild staff member reached out to her via LinkedIn, asking whether kids could help out. Fairchild organizes annual challenges to foster science exploration.

Massa said the idea seemed great because her team isn’t big enough to grow every single plant on Earth to test its viability for space, and all plants behave differently. It started with a few schools with about 50 kids, it’s now spread nationally and even internationally to nearly 500 schools with hundreds of thousands of students, spreading to countries such as Australia and South Africa.

“We have developed this type of student army around the country and world to help us do it,” Massa said. “We’ve seen a tremendous amount of success.

“It’s really a triple win. We have students doing authentic research for NASA, NASA getting data from this research that we can use, and teachers having this program where they can have this wonderful way to teach.”

How does Growing Beyond Earth work exactly?

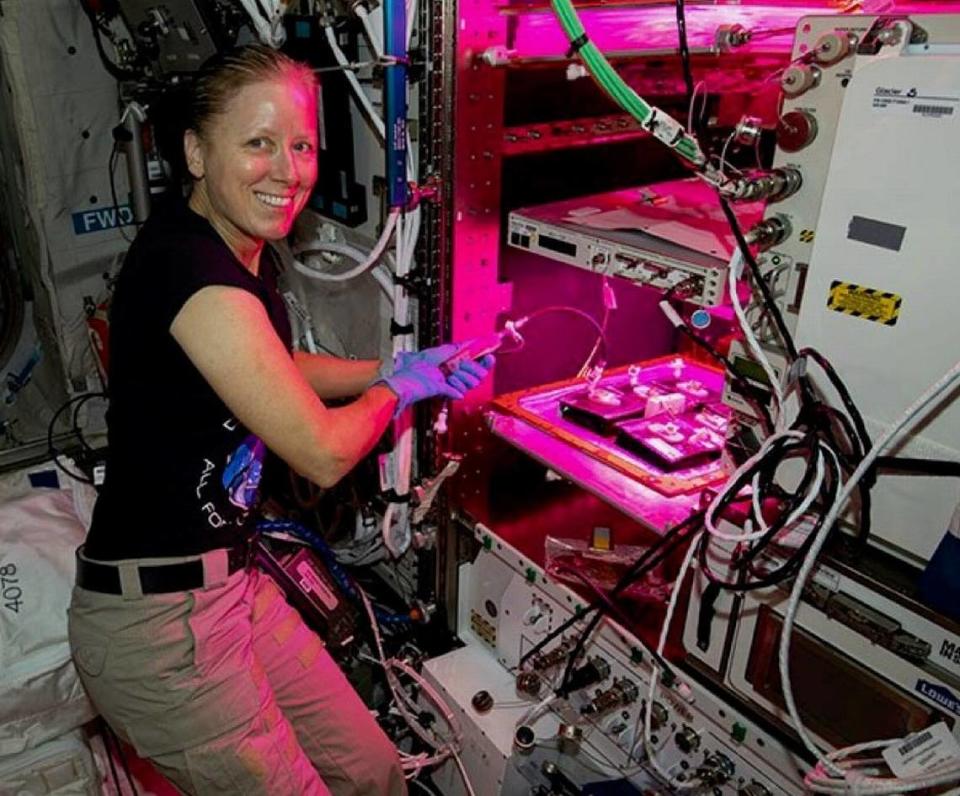

Massa and her team experiment with edible plants — or pick-and-eat plants — to see how they would behave in space and whether astronauts could eat them, she said. They first test them extensively on Earth and then send them to the Vegetable Production System (Veggie), a plant growth unit on the ISS.

Growing Beyond Earth takes their endeavor to a larger scale, with more people studying more plants at a quicker pace. Fairchild handles the logistics that turn science classrooms in Miami-Dade and beyond into tiny laboratories. The garden’s staff ships the seeds and the equipment needed to grow them, mimicking NASA’s procedures as much as possible.

Students have studied radishes, and herbs like dill and cilantro. They record how much water they add, their height, how many seeds germinate and other details.

The best part, Massa said, is that because of the variety of locations, NASA gets data on how plants behave in different climates from arid to humid, and different altitudes from Denver’s mountains to Puerto Rico’s seas.

NASA experts use the data produced to decide whether a plant is a good candidate — usually they’re looking for a plant that doesn’t take up a lot of space but that still produces a lot of food. If they find one, they test it themselves. If it keeps succeeding, they eventually will send it to space.

Because of GBE, some plants that NASA personnel would’ve never thought about made it to the orbit, Massa said, like a type of lettuce. The ISS has also implemented strategies started in GBE classrooms, like a new leaf vegetable harvesting strategy that involves frequent harvesting as plants grow.

Saturday’s symposium, the key annual event, in Fairchild

Massa said students can take their experiments further than the basics NASA requires if they want.

During one summer, she interned at Fairchild and created a microgravity simulator, or a mechanism that mimics the condition where gravity seems to be very small.

Carl Lewis, the director of the Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, said that type of expansion happens thanks to the garden’s innovation studio called the Makerspace. There, students can draw whatever artifact they envision and then produce it with a 3D printer.

“It enables them to turn ideas into reality,” he said.

What he like most though is watching students grow, especially at the annual Growing Beyond Earth Student Research Symposium.

“What’s exciting is this is when the students get feedback,” Lewis said. “When they present some new discovery that they made in their classroom and then hear from an administrator from NASA that that discovery is going to help ... that’s really tantalizing for everybody.”

Gonzalez, the 18-year-old, sees that impact both ways. Because of GBE, she became so passionate about science that she decided that’s what she wants to do for the rest of her life. After graduating, she’ll attend the University of Florida and plans to major in plant biology.

“A lot of people see plants as something you see grow and whatever,” she said. “They adapt to different environments and different things. Just a little more water can make them respond a certain way. They respond to whatever you give them. To me, it’s beautiful.”